RELATED STORIES

AUTHORS

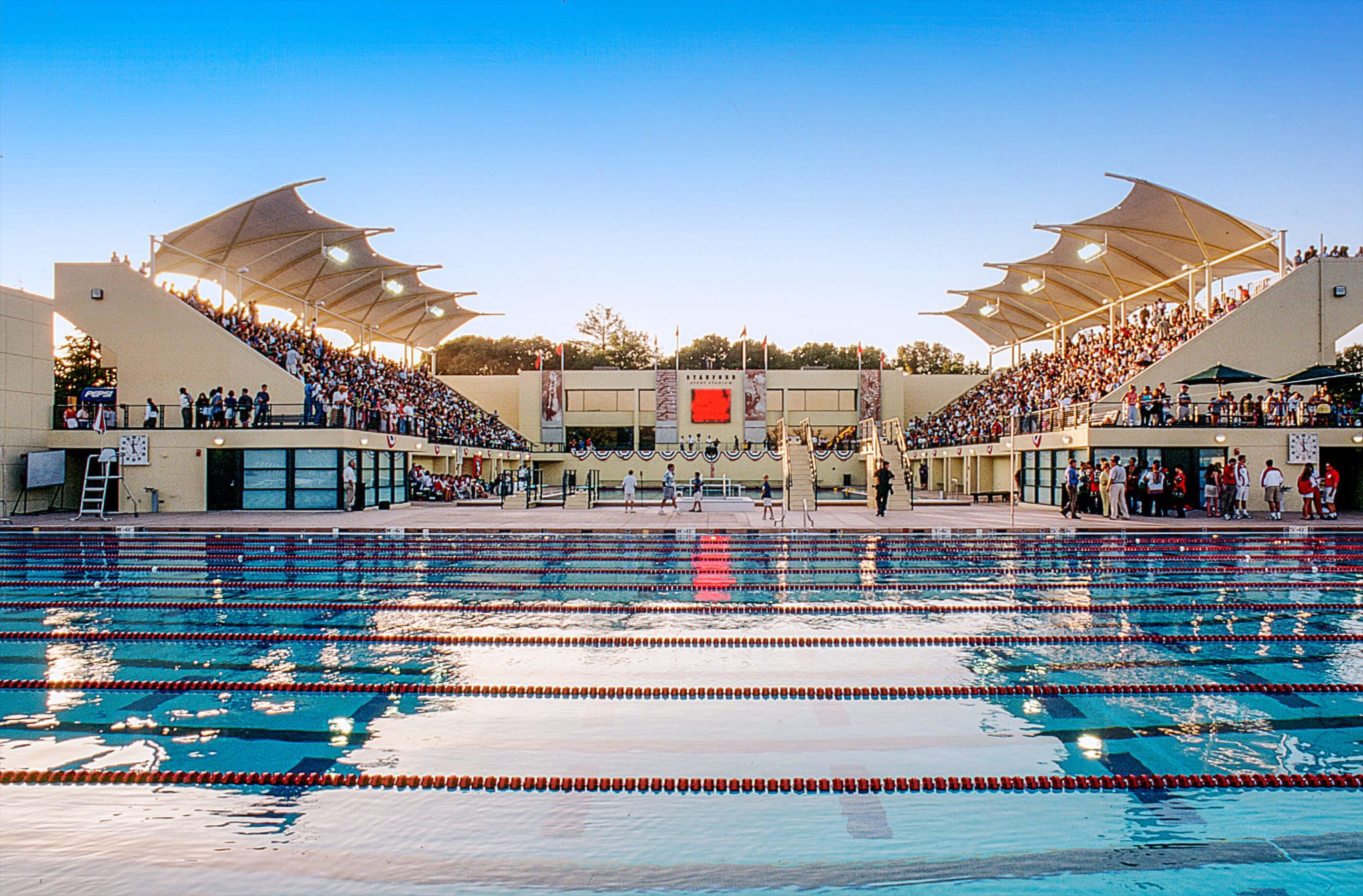

Student athletes thrive on the cheering crowds.

I attended the national water polo championships at UC Berkeley’s Spieker Aquatics Center in 2011 and at Stanford’s Avery Aquatic Center in 2013. I like to see how colleges and universities are actually using their facilities and managing big events, because it helps feed our design thinking. Watching big water polo events like these are particularly revealing because very few swim facilities in the country are designed to host large-scale national events.

Spieker Aquatics, which opened in 2009 and was part of the historic Harmon Gymnasium and Swimming Pool complex, has seating for 800 with room to accomodate 1,700 temporary seats. I’ve been there before to attend dual meets, in which two teams compete against each other, and see practice sessions, but nothing like a national championship. Spieker is primarily a venue for training and is not designed for large numbers of spectators.

Mike Huff, the assistant athletics director for facilities management, and his team at Cal were able to transform this facility into a spectator venue within a handful of days. They trucked in seating for an additional thousand spectators and created comfortable places for event officials, press, and concessions. The transformation felt seamless and looked natural. I was reminded how much the event makes the venue rather than the other way around.

What architects tend to design—the permanent architecture—addresses the needs of the competitors and the spectators. We aim to make sure that the event feels intimate for the people watching it. In order to build electricity and fill the competitors with energy, it is important for a lot of fans to be right there on the deck, close to the swimmers. Design ingenuity is required so the facilities can grow and shrink without the change being too noticeable.

That’s particularly challenging with large venues. The Avery Aquatics Center ELS designed at Stanford University is an example. We renovated and expanded an existing pool complex so it could accomodate water polo events as well as nighttime events. It can handle Olympic training and seat 2,400 people for big events. When the university hosts nighttime water polo games, the place is packed. The horseshoe design, which puts spectators on both sides of the pool, helps keep the energy high. Student athletes thrive on the cheering crowds.

But much of the time, Avery Aquatics Center is just used for practice. So we worked to design everything—the lighting, the shade structures, the seating—to keep a sense of intimacy so it doesn’t feel cavernous and empty for everyday use. This is accomplished by providing the appropriate number of seats for conference dual meets and matches, as opposed to providing permanent fixed seating for a national or international event, which may take place once every three to five years and require an additional 1,000 seats. For such an event, the complex can “flex up” to include additional temporary seats similar to the way Spieker Aquatics Center does.

ELS is currently working with university and athletics administrators at the University of Southern California (USC) in Los Angeles on renovating and expanding their campus aquatics venue, the McDonald’s Olympic Swim Stadium. We’re adding stadium seating, student athlete amenities, coach offices, extensive dryland training zones, and multipurpose space for USC Recreational Sports. We are taking what are essentially two existing competition pools and building a competition venue around them. The facility will house events ranging from 700 to 2,500 fans.

These facilities are a key part of recruiting student athletes from across the nation and globe. The facilities need to equal the quality of the coaching as well as the reputation of the university.

The front door of the new stadium has a prominent frontage on McClintock Avenue, one of the main north/south pedestrian routes that crosses the USC campus. McClintock Avenue connects multiple intercollegiate athletic venues throughout the campus, including the football practice facility, Loker Track Stadoim, Dedeaux Baseball Stadium, and the nearly completed John McKay Center for Intercollegiate Athletics.

The dominent architectural aesthetic at USC is Romanesque, as interpreted throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. These forms provide cues that can be translated into contemporary design. The buildings focused on McClintock Avenue will relate more directly to the existing architectural fabric, while the internal program areas are more modern. While the new USC intercollegiate aquatics facility is state-of-the-art, it was important to be both contextual and respectful of the campus’ rich design vocabulary.