AUTHORS

Pencil & Mouse: Notes on the Art of Sketching

by: Anthony Grand, AIA, LEED AP BD+C

TOPICS DISCUSSED:

Before computer-aided drafting came along, drawing was an integral part of architecture. These days, architects are far more likely to wield a mouse than a pencil. Even those of us who love to draw don’t do it as much as we used to.Architecture

But drawing sharpens the way you look at the world. Drawing still helps you think. And it can still be a useful way to get to a design.

Photographing places and posting photos online is certainly popular now. But the photo only tells you that you were there. A drawing is a deeper record of what you really saw. When you go out and draw something—whether a person, a building, or a landscape—the world slows down. You have to really pay attention, to observe, just to figure out where the light and shadows are. Then you remember what you’re seeing a lot more clearly. When I look at any of my old travel sketches, even those from 20 years ago, I can recall exactly where I was when I was drawing them. The more you draw, the more you develop a language—a way to abstract and organize what you are seeing into lines on the paper.

When I place the first line on paper to capture the dream, the dream becomes less.

The same factors are at play when you start designing a building. You usually start with a line or a tangle of lines. To quote Louis Kahn, “When I place the first line on paper to capture the dream, the dream becomes less.” I think it also becomes focused. You have to first start, and then the process becomes a cycle of continually refocusing and organizing your ideas.

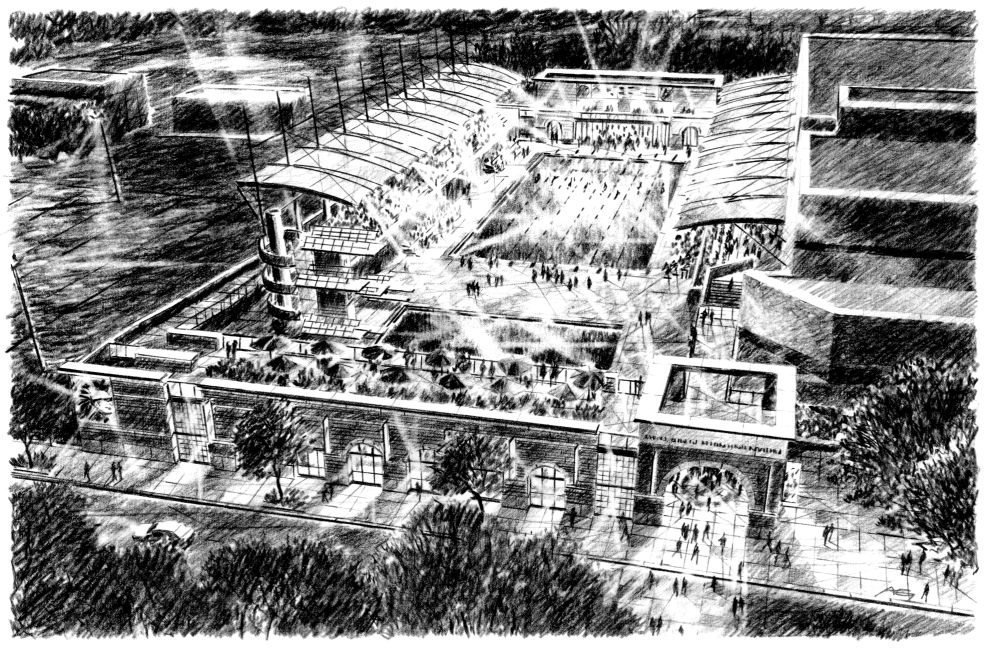

At the beginning of our design process, I’ll often start with sketches. For example, recently we interviewed for a potential project at a university. Over the next day or so I sketched out key views and annotated ideas, creating a storyboard of the walk through the site. It helped us clarify our thinking and hopefully communicate that to our potential client.

Lately I’ve also been designing digitally a lot. But I still often go back and forth between the computer and paper. I might start by roughly sketching out the idea by hand, building a quick 3D model, then drawing again. The model is also good for setting up views for potential renderings. Once I’ve got a good view, I’ll print a very basic version, just lines, and draw over that, trying different things. Then I’ll go back and perhaps change the model and adjust the views. So it’s a continuous dialogue between the two techniques.

Sketch by Anthony Grand. AIP 21 Award, 2006

To create a digital model, you have to work out a lot more ahead of time—because the software can’t do everything. Whereas with drawing, you don’t have to figure out as much in advance. It can be more intuitive. The combination of both seems to be both a successful way to design and a way of setting up views for further illustration. As for what we show the client, it depends. Some clients like the hyperrealistic digital version. For others, a pencil rendering is better, because it doesn’t look set in stone and allows for some imagination. I’d also like to think that it reveals a “hand” behind the lines.

Hand drawing may be going out of fashion, but I hope there are some young architects who still take it up. While designing, I think that it’s still a good way to both organize and present your thoughts: a beginning of a dialogue. One sign that the art of sketching is still thriving is the nonprofit organization Urban Sketchers. Founded in 2007, it aims to promote location drawing by featuring the work of 100 invited artists on its website.

The works run the gamut from the rough to the refined—some people have great hands, some don’t. But they all took the time to record something they felt was important. Something they wanted to remember.

AUTHORS