Reflections on a Pre-Lockdown Grand Tour

by: Emilio Ponce

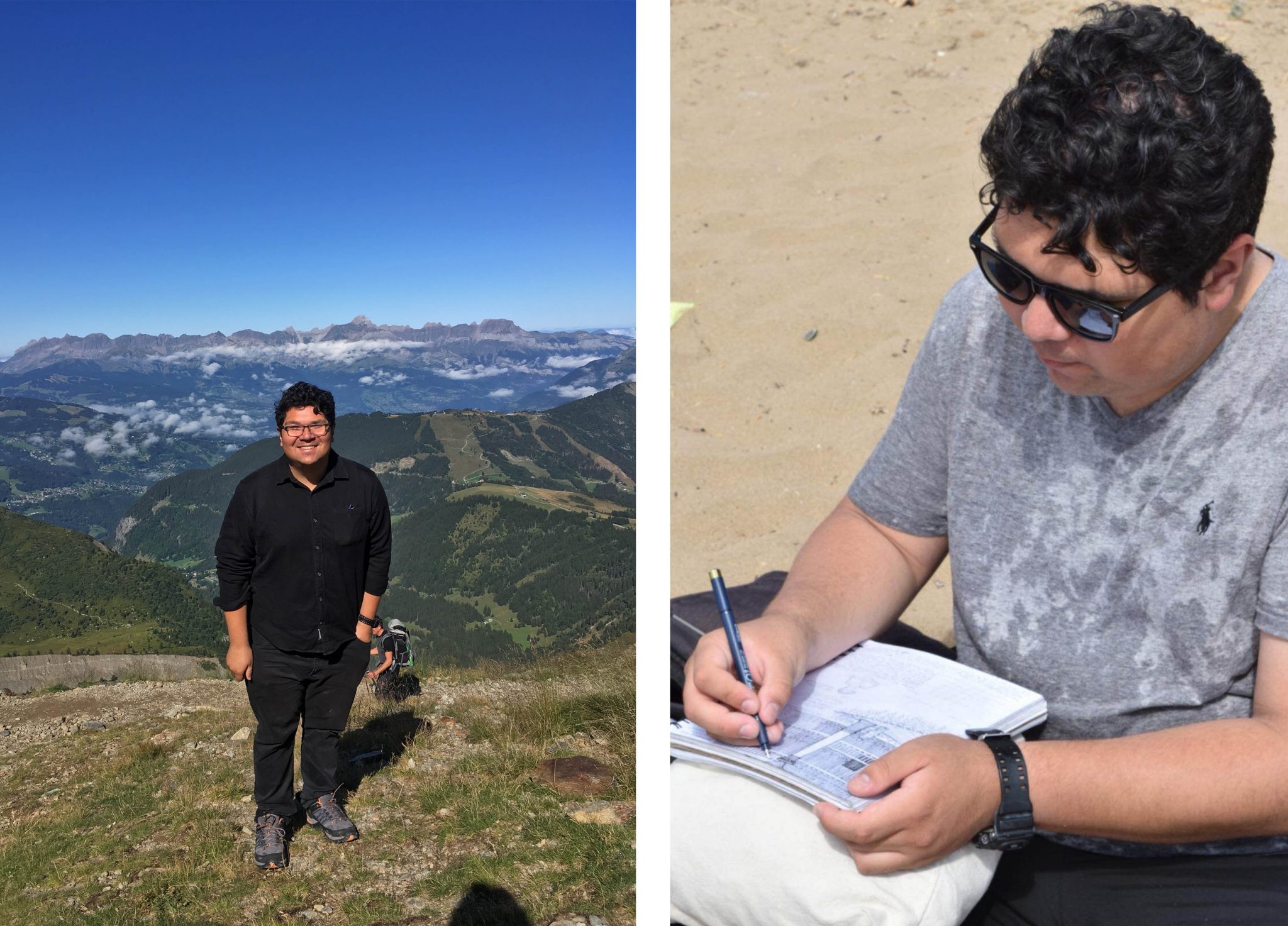

Before starting my career there with a full-time job, I embarked on a month-long trip across Europe — my first time on the continent — to explore its architecture, art history, and culture. The trip itself was of course spectacular, but the experience has since taken on a whole new layer of meaning. As I reminisce on our optimistic, pre-lockdown world, I am confronted with the challenges of this extraordinary time, whether they come from climate change, systemic racism, or the pandemic. I am grateful that you’re joining me as I reflect on what aspiring architects like myself can do to address this moment.

History and Context

Beginning in the 18th century, English aristocrats supplemented their education with years of travel throughout Europe, a rite of passage that became known as the Grand Tour. In 2019, as part of a study-abroad group composed of other students from across the UC system, our travel guide — a cicerone — brought me and 23 others to London, Paris, Chamonix, Rome, and Pompeii, where we followed in the footsteps of Grand Tourists before us. None of us have a royal background, but in our studies, our group felt truly noble. By documenting my travels through sketching and journaling, I came to know what someone on the Grand Tour might have felt like. As the first college graduate in my Latino family, I felt especially proud of my accomplishments. But with only a handful of months before the pandemic emerged, I had no idea just how lucky I was.

Borough Market, London: Distant Delicacies

During my internship at ELS, I was able to hone my sketching and note-taking during site visits and community meetings for several historic rehabilitation projects in the East Bay. My European trip turned out to be the ideal venue for practicing those skills again at a much larger scale, starting with one of my first outings, to the Borough Market in London. In 2019, this was a bustling, sensory-rich place, where delicious aromas fill the soaring spaces. It’s a little different now, but still, in our socially-distanced era, high-ceilinged public spaces like these offer a kind of compromise, with an architecture that provides plenty of light and breeze while allowing for the continued operation of its essential spaces.

While the wholesale and retail market’s history dates to the 11th century, it was moved to its current site in the mid-1700s. Later interventions have expanded the public experience. At pop-up tents with charming umbrellas, guests try out samples below tiny planters that climb around the structural columns as if they were ivy. The spacious hall offers outdoor seating and takeout for people who would rather not stay too long. (Apart from all the downsides of take-out, I’m glad that it promotes the activation of local public spaces and the safety of its workers in challenging conditions.) Even more importantly, I enjoyed an amazing panini here. Without question, I will eat here again.

Musée d’Orsay and Palais Garnier, Paris: Virtual Museums

After arriving at our hotel in Paris, we set out on foot to explore the city. We started with the Musée d’Orsay and the Palais Garnier, which exemplify the impressive design of their respective eras — so much grandeur that my outdated iPhone can’t do justice.

Today, with museums either still closed or open but under challenging conditions, the digital world represents a compelling version of the visitor experience. Rather than let their resources turn into a closed vault, leaders at the Musée d’Orsay (among other institutions) have opted to digitize their marvelous holdings through Google’s Arts and Cultures program, folding their real-world presence into the safety of home.

I can’t help but imagine what would happen if this program were adopted by more venues and integrated into an immersive experience that offers users VR-style mobility well beyond the limitations of the program’s current app. Documenting existing structures is integral to the design process for architectural project sites, but why shouldn’t this process be expanded to every important historic landmark, especially those at risk from climate change and wear-and-tear? Digitizing these places — bringing them into the Internet canon–could offer today’s visitors a sense of the site’s scale, materiality, and light. It would improve accessibility for people with disabilities or for anyone whose health issues or finances prevent an in-person trip. To be clear, there’s no substitute for the real thing, so I don’t think wider adoption of this program would hinder real-world attendance. If anything, it would help. With the ability to do a kind of Grand Tour online, curious users have an even greater incentive to see a site in person, whenever that time comes.

La Mer de Glace, Chamonix: Fading Memories

La Mer de Glace is an extraordinary glacier cave in Chamonix, France, at the foot of the towering Mont Blanc. And its very existence is threatened. On our flight of stairs down the mountain, markers indicate how the height of the glacier has dwindled in size year after year. The frequency of these markers accelerates as visitors approached the bottom, making each step down a painful visualization of climate change itself. It was a pensive and somber experience.

As wildfires scorch California and hurricanes roar through the Gulf coast, the preservation of our natural resources has never felt more vital to me. Whether it’s a graceful and frigid glacier or a gargantuan redwood trunk, it can all disappear so easily. That’s why I believe designers must find ways to tell stories that spur more meaningful, personalized action. We just can’t get used to this version of normal. Imagine how disappointed those Grand Tourists would be if they heard these incredible masses of ice would one day shrink to the size of a small valley.

Shoreditch District, London – Sacred or Sacrilegious?

During my stay at London, I visited the Shoreditch district, where thick layers of paint and wheatpaste posters gave off a radiant, nearly spiritual ambience. This felt like a place where artists can create as if it were their religion.

Once devoted to furniture factories and bomb-battered during World War II, Shoreditch has undergone significant changes in recent years. Old industrial buildings now hold cozy lofts and spots for delicious artisanal food. Facades are the site for a dizzying, clashing blend of historic architecture and street art. As seen through its tight corridors and irregular lots, unintended programs emerge — such as a public art gallery, a food truck spot, a DIY skatepark, or a runway for Instagram models.

The overlapping, constantly overwritten nature of street art keeps its messaging relevant in rapid-fire fashion, similar to the news cycle of our information age. In Shoreditch, I felt like I was in a modern-day agora, where, at the scale of the street, people could gather to engage in artistic, spiritual, and political discourse.

These spaces are not perfect, of course. I’m overlooking the challenges of private and public property, vandalism, and preservation. Still, Shoreditch is a powerful example of what can happen when residents, designers and owners allow artists to share their side of the story, and then just stand back. These narrative-based spaces help people make lasting visual contributions to their neighborhood and to the wider urban context — just as sketching and diagramming have strengthened my ability to focus on details in our environment that typically go overlooked.

Closing Thoughts

It’s early fall of 2020. I’ve fast forwarded a year and I’m on the opposite side of the globe, working from my parents’ house. Artists in Downtown Oakland use the plywood barricades on businesses as a surface for murals on justice for George Floyd, and in San Francisco and Washington, D.C., bright, bold letters reading “Black Lives Matter” cover the roadways. All over America, underrepresented voices ripple through the built environment at different scales, giving a timestamp of this moment. However, these acts aren’t enough to provide necessary systemic change.

To me, the nexus of COVID-19 and the evolving struggle for racial justice urges us to consider our role as designers more fully and urgently. How can architecture and urban design, which can perpetuate systemic racism, become agents of social justice for marginalized communities? I want to see a future where these communities exert control over their own urban spaces, and in so doing, help liberate people from embedded oppression.

That future is why the memories of my Grand Tour have hit me so squarely. These experiences, considered today, have helped me connect the design of spaces to social context in surprising new ways. My trip to Europe didn’t just challenge me to look more closely at what I’m seeing. Here in the US, it has led me to find out what I’m not seeing — and to question the built environment I’ve grown so accustomed to. I can’t wait to find out where I go from here.