RELATED STORIES

AUTHORS

Ask retirees, homeowners, renters, landlords – in one way or another, everyone is feeling the impact, for better or worse. The cause of the crisis is also the effect: there’s not enough housing to go around. Here in the Bay Area alone, the California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) forecasts a deficit of almost a half-million housing units through 2031. Revised every eight years since 1969, the state’s Housing Element Law has been a way for our cities and counties to make plans that, in theory, meet the housing needs of everyone in their community by removing barriers to the construction of housing. In the current sixth housing element cycle, HCD has tightened the requirements for achieving certification: no longer can cities include housing element sites that show little promise of becoming a reality. HCD now requires jurisdictions to provide a higher level of review and analysis to sites smaller than half an acre and larger than ten acres. It also requires that any sites with existing occupied units provide a displacement plan that relocates existing residents. While these updates to the Housing Element will help encourage development, it seems clear that the state is still relying on private development to produce the actual housing units. This is one example of larger problems that cannot be solved through private development, such as growing income inequality, wage stagnation, rising inflation, elevated construction costs, and few resources for those that fall out of homes and contribute to the increasingly intractable problem of homelessness.

Meanwhile, the number of people experiencing housing insecurity has grown, as the middle class moves out of the growing gap between the wealthy and poor. San Francisco has received national attention for its deepening challenges with the unhoused, which stem partly from a downtown that has been hollowed out by Covid-era closures – San Francisco still has one of the highest office occupancy vacancy rates in the country near 35%. Over the last year, we’ve seen rising interest prices put homebuying even further out of reach. The prospect of giving up a low-interest mortgage has brought listings to a crawl as current owners look to stay put. Even though fewer people are looking, available housing supplies have plummeted, and the cost of financing a home remains staggeringly high for would-be buyers.

Amid all this, we at ELS, headquartered in Berkeley, must ask ourselves: what can we do to help our region add housing? While the Bay Area has been a nexus for these challenges, it is also fortunate to have countless designers, developers, and municipal officials who are creatively tackling the problem head on. When it works, it leads to the creation of new units where the construction type works out financially, public perception is positive, affordable housing requirements can be met, and material costs, loan rates, and timing all work out. It’s nothing short of a miracle when all those factors come together in a single project that results in a finished project. The combined housing stock that is built each year has not been enough to meet housing demand historically, which is why we are at a deficit approach half a million homes in the Bay Area.

It’s imperative that all of us in the design community work together with municipalities and directly with developers to create housing that forms part of the solution. We call this “housing at the edges,” which refers to the neglected spaces and ideas for increasing access to housing that have been overlooked and can play a part in the larger solution.

What are we doing at ELS to push these edges closer to the middle? We are attacking this problem in four key ways: through helping change policy at the City level, by working with cities to improve shelter design, looking for creative solutions that take advantage of the hidden opportunities that lie at the intersection of policy and built form, and through advocacy among our creative partners.

Historically in the Bay Area and much of coastal California, housing development has been slowed by anti-housing advocates that use the local design-review process as a cudgel. This allows people – sometimes even a single person – to shrink a development to the point where it is no longer financially feasible. The project can also be rejected outright or be burdened with such onerous provisions that it’s not possible to continue the work. In response, the State has passed a series of bills over the past five years to tackle the problem. They support the creation of additional units on single-family lots (Senate Bill 9), allow density increases of up to ten units when the project is near jobs and transit (SB 10), prohibit reductions in housing areas (SB 330), streamline the creation of accessory dwelling units (Assembly Bill 881) and facilitate affordability through streamlining initiatives such as SB 35. Under streamlining legislation, cities are required to enact objective design and development standards for development proposals that qualify. ELS, working with our partners at two like-minded firms (EMC Planning and Urban Field Studio), has assisted a number of Bay Area cities on two fronts: first, by providing our expertise in evaluating housing element sites and secondly through the development of Objective Design and Development Standards (ODDS).

Typically, multi-family projects would be required to go through a Design Review process where existing municipal codes would be interpreted and applied. During that process, project opponents are able to take advantage of subjective standards in ways that effectively kill the proposal. This story is all too familiar across the Bay Area, and it is one of the principal reasons the region remains so short of housing. Yet in places where some of these state bills overlap with the requirements of the ongoing housing element process, the combination can push many communities into a challenging position in which “builders remedy” projects are submitted for approval. If the municipality has not already established Objective Design and Development Standards, developers have a legal window for the proposal of projects that have little planning and design oversight. Outcomes like these aren’t helpful to solving the crisis. Through our work with developers and cities, we have gained a dual perspective that shapes our thinking on how best to approach the issues pragmatically and in ways that lead to buildable, community-oriented housing. This includes understanding the intersection of construction types as they relate to financing and planning code. Working with Ryan Call, a former ELSer who is now with Urban Field Studio, we’ve studied historic building patterns in each location we develop ODDS. This helps us understand the vernacular particular to a place. People often attribute the feel of a place to the size, shape, and cosmetic details of its buildings. But there are other forces in play that contribute more to the quality of an area:

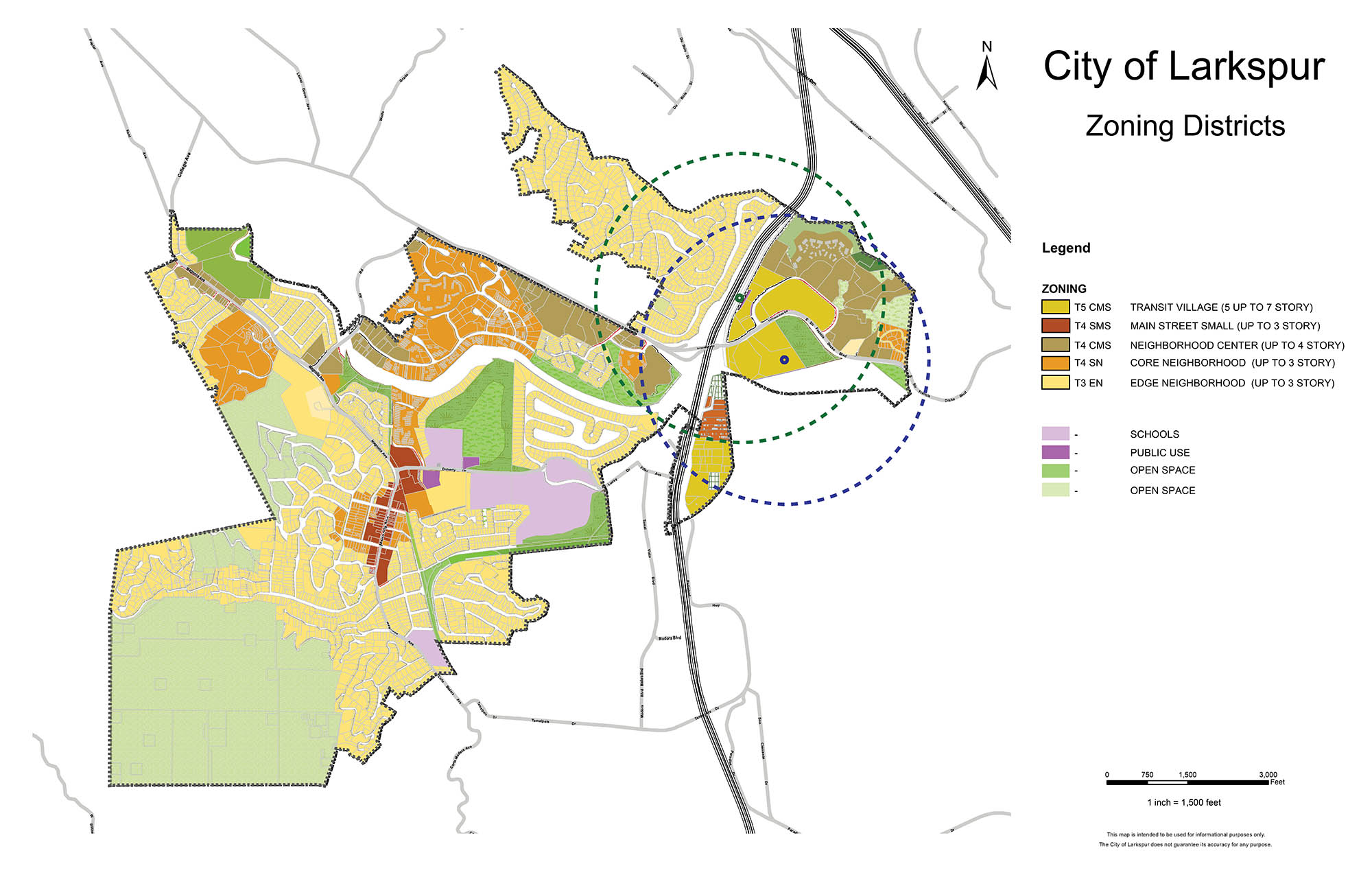

As part of the ODDS process, we study existing development patterns in each city where we apply our proposed standards (including Larkspur, as above). This work helps us predict their effectiveness in creating appropriately scaled development and ensures that we can provide enough flexibility for developers to approach a site in ways that lead to actual construction. It’s relatively simple to evaluate the prospects of a rectilinear three-acre site for development, but such sites are rare in the Bay Area. Our studies include the number of possible units and evaluate the construction type necessary to maximize the site when considering topography, shape, and the achievability of parking goals. Our entire approach to developing ODDS focuses on buildablility. For example, in today’s construction climate, it’s challenging in most locations to build concrete podiums with wood framing above (Type V over Type I); the most achievable development is often townhouses, which don’t bring a level of density that helps most communities towards meeting their goals. Housing sites do not turn over often; it’s critical to provide a pathway to development that can impact the housing crisis while fitting in within the surrounding urban fabric. Allowing a site to become a low-density development will leave that parcel underdeveloped for decades or longer. Projects that aren’t feasible financially when considering all the factors will not contribute to helping us meet our long-term regional housing goals.

As part of the ODDS process, we study existing development patterns in each city where we apply our proposed standards (including Larkspur, as above). This work helps us predict their effectiveness in creating appropriately scaled development and ensures that we can provide enough flexibility for developers to approach a site in ways that lead to actual construction. It’s relatively simple to evaluate the prospects of a rectilinear three-acre site for development, but such sites are rare in the Bay Area. Our studies include the number of possible units and evaluate the construction type necessary to maximize the site when considering topography, shape, and the achievability of parking goals. Our entire approach to developing ODDS focuses on buildablility. For example, in today’s construction climate, it’s challenging in most locations to build concrete podiums with wood framing above (Type V over Type I); the most achievable development is often townhouses, which don’t bring a level of density that helps most communities towards meeting their goals. Housing sites do not turn over often; it’s critical to provide a pathway to development that can impact the housing crisis while fitting in within the surrounding urban fabric. Allowing a site to become a low-density development will leave that parcel underdeveloped for decades or longer. Projects that aren’t feasible financially when considering all the factors will not contribute to helping us meet our long-term regional housing goals.

In many of our communities, we’ve seen tent and RV encampments grow in unused public space. In the West, these encampments cannot be legally cleared unless they were provided with shelter to move into. This is based on a 2018 decision by the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals against the City of Boise, Idaho. What is the best path towards providing housing that incentives people to get off the street? When considering the design of shelters, it is important to consider the difference between congregate and non-congregate housing. In the former, individuals are housed together in large common rooms with little privacy. In the latter, a city will use hotels, motels, and dormitories to offer each individual or family a living space with more privacy and separation from adjacent residents. The unhoused turns down congregate beds at a very high percentage; residents vastly prefer non-congregate living, which afford residents more privacy and helps prevent the spread of communicable diseases including Covid-19. Unfortunately, providing such housing remains difficult – but there are inspiring examples nonetheless. In California, Project Homekey, a statewide program, has seen great success in bringing non-congregate rooms online quickly. Through a highly successful program in San Jose, the city provides non-congregate modular housing through the identification of sites that have gone unused by the city, CalTrans, or the broader county. ELS has partnered with the city on these Emergency Housing projects at Evans Lane (for families) and at Guadalupe Parkway and Rue Ferrari (for singles and couples); we are now embarking on a project to provide safe off-street parking solutions for those living in recreational vehicles. Usually, when these developments are publicized, the project’s neighbors express concern that these sites will attract increased drug use, crime and calls to the police. But as a recent KQED article outlined, the opposite was true: drug use and 911 calls decreased almost uniformly across these sites, once they were open. What the City of San Jose and our team has been able to do at these sites is less about building a traditional shelter; instead, we focus on creating places where a community can grow. All sites include dog runs, community gardens, and outdoor recreation areas; the family sites include playgrounds. Community buildings include shared kitchens, laundry facilities, and open-ended space. When you walk around these communities, you don’t see a shelter, you don’t see people trying to survive, you see people communicating openly and making the most of their lives.

As part of our design approach to these sites, we’ve implemented color schemes that provide interest and cohesion, while not painting all units the same color. Using color in this way cues residents to read their unit as an individual place that is effectively separate from the others. Other simple design approaches reflect an deeper layer of consideration that helps these places operate as the livable – if transitional – communities they are.

The housing crisis is such a large problem that it can’t be solved with one solution, even if one can be applied at a large scale. That’s why we all need to work towards our own creative solutions. Project Homekey, for instance, has been a great way to bring housing online quickly, but the number of opportunities is limited. The Emergency Housing effort in San Jose, while also highly successful, is likely to falter in a smaller, denser city like Berkeley – there just isn’t enough public land at the needed scale. In fact, so much of the Bay Area is built out that primary solutions will need to come from densifying our existing population centers. One approach the State has taken is SB 9. Championed by the Bay-Area based Casita Coalition, the bill clarifies the path to developing Accessory Development Units on single family lots. ADUs are still costly, and initially, many homeowners hoped to offset the cost of these units in the immediate term by offering them as short-term rental opportunities through Airbnb and others. Many cities such as Berkeley closed that door by requiring all new ADU’s to have deeded restrictions limiting rentals to no less than 30 days, effectively cutting off potential revenue that would pay for the unit. Another bill, SB 10, allows single-family lots to be redeveloped into multifamily projects of up to 10 units, although the law leaves it up to each city to decide whether to allow ministerial approvals. In moving us towards the goal, these are small gains, but they are critical to the effort.

Many observers have dismissed workplace conversions when they are based on typical modern office buildings with massive floorplates and advanced curtainwall systems. The costly challenges of replacing the skin on a building, running all the additional utilities, and (potentially) adding a central lightwell or courtyard tends to deter most developers from the effort. However, older, smaller office buildings are a real option. Many already have operable windows and the floorplate depth is more in line with residential design needs. Just as warehouse conversions turned loft buildings into highly desirable residential units, these office buildings could be an interesting alternative, especially when their higher interior ceilings and large windows distinguish a property from the standard offerings in the residential rental and sale market.

For an example of a workplace conversion, we decided to look nearby – very nearby, at 2030 Addison Street, the space that ELS designed in the 1980s and which now currently holds roughly half of our Berkeley headquarters. (The other half is at 2040 Addison Street.) This is a narrow building, just a block away from the Downtown Berkeley BART station, with a small floorplate at the ground floor that allows for a public mid-block crossing. The form then expands once it gets to the second floor, where our office space is, and it stays that wide for the rest of its five stories. Even at its widest, the building is a very manageable 50’ x 120’ with glass on three sides and a side core with two elevators and stairs. There’s a logical vertical path for bringing in additional services, and each floor could be divided into three to four units, for a total of 15-20 units – all while leaving intact the existing second-floor office and ground-floor retail space. If we assume the units are 85% market rate and 15% affordable, the project could offer seventeen market-rate units and a modest three affordable units. The development’s overall environmental cost is persuasive, delivering significant savings in embodied carbon by saving the existing structure, shell and skin – much more practical than demolishing and constructing a residential mid-rise from scratch.

Conversions like these don’t come without hidden costs. A change of use triggers a seismic evaluation that will most likely lead to a full seismic retrofit if the building has never received one. But like many office buildings, 2030 Addison is built from steel construction which would not require structural acrobatics to achieve. The opportunity for unused older offices in the Bay Area near BART to turn into residential is a potential untapped resource.

As design professionals, we can see the key issues that drive the affordability of today’s developments and are pushing municipalities to rethink standards that benefit no one. And there is no more counterproductive and costly standard than parking requirements. Development sites in the Bay Area are small, irregular, and expensive. When cities mandate high parking counts that include multiple parking spaces per unit – often adding a high ratio of guest parking spaces – they effectively kill their own developments before they’ve gotten off the ground. Development is a math problem, and parking too often unbalances the equation. Imagine a three-story multi-family building on a one-acre lot, generating 25 units at an average of 900 sf per unit. A typical surface parking lot in California averages about 400 sf per space when considering not only the 9’ x 18’ space but the associated drive aisles, landscaping, and bioretention requirements. If two spaces per unit are envisioned, that’s a 20,000 sf lot for just 25 units. All that inefficiency comes at a profound opportunity cost, especially in dense urban environments where development opportunities are few. By reducing the parking requirement to one space per unit, our hypothetical project needs a more manageable 10,000 sf of parking surface – which potentially enables the addition of 15 more units to the site.

Another issue comes from surface parking. Paving half of our hypothetical site as parking would cost around $750,000. If the building grows larger to accommodate ten more units while maintaining the higher parking requirement, the available surface can’t handle the increase in parking, requiring a parking structure instead. But now, instead of $15,000 per surface space, it’s $32,000 for each structured space. And what if – due to the hypothetical city’s minimum — we needed 1 guest space for every 4 units on top of the two spaces for each of the 35 units? The cost would now be $2.5M, likely too much for a project budget to bear. Our stance is that through zoning reforms, developments would be allowed to bypass minimum requirements and put in place robust systems that enable shared parking between certain uses, while also encouraging car shares and other creative solutions to reduce the vehicle miles traveled impact associated with the project. When developers are allowed to think creatively, they are empowered to deliver a project that pencils out and meets the demand.

Together with EMC Planning and Urban Field, ELS has been talking to communities in Cupertino, Fairfax and Larkspur to rethink parking and design requirements in ways that are more equitable and better serve the region’s goals. Rather than dictate minimum parking requirements, we advocate for removal of minimums and the placement of caps on maximums. In other words, let the local market decide what the local market can bear. We advocate the elimination of guest parking requirements, and for more shared parking allowances. Where parking occurs, advocate for placing it behind buildings to preserve a walkable street front. This type of advocacy helps ground local government decision making in real-world realities so that zoning is not detached from the very projects the Housing Elements are designed to spur.

ELS has a significant personal stake in this fight. Almost all of us live in the East Bay or San Francisco and have seen how high rents and $1M+ home prices make it difficult to attract new colleagues. Many of us came to the Bay Area for the same reasons everyone else is coming here: the great art, remarkable culture, fabulous food, and the educational and professional opportunities. Unfortunately, the housing crisis has eroded many of the things we cherish. Where, for example, does the barista at the nearby coffee shop live that doesn’t require a two-hour commute? How do we maintain an arts culture in a place where artists can’t live? How can we maintain vibrant outdoor shopping and eating districts when the unhoused community has moved into that space? How can we continue to attract the best and brightest with some of the highest living expenses in the country?

The answer to all of these is that everyone who lives here plays a role in the success of housing production, approaching the problem from different perspectives, and advocating for better solutions. I have no doubt that we’ll get there.